I spent much of my youth in involuntary servitude. First, to my father, who put me to tending the lower forty and digging holes in order to fill them in again after removing the rocks, which I moved by wheelbarrow from one place to another. For this I received a lousy two bucks a week and a desire to avoid manual labor for the rest of my life. I got another two bucks a week from Mr. Dixon down the street, for whom I'd mow a lawn that went on forever each Saturday morning, a sacred time of freedom for most kids. I clearly remember working one spring and summer week after week for Mr. Dixon and foregoing the usual payment in order to trade for a portable tape recorder his son had grown tired of playing with. Dixon must have thought of himself as a wheeler-dealer, but I became a collector of sounds, so I got the better deal.

There was another benefit to working for Mr. Dixon; he made periodic trips to the local dump.

Our local dump was a cut above most. They didn't take garbage. They wanted your junk. This was a time before lawyers and litigation ruled the land, so if you paid your way into the dump, you were allowed to climb up on the mountain of junk, grab what you wanted and take it home with you. In this manner I procured my first radio and later, my first television set.

The radio was like any radio, except that it was mine. I used it to tune in Jean Shepherd on WOR when I was supposed to be sleeping. It's secondary job was to bring in the Good Guys of WMCA. But the television, it was something else again. When you turned it on, you'd hear the tubes crackle to life and smell the unmistakable odor of electrical ozone. But the screen would stay black. This I surmised was the reason it ended up in the dump. The poor people who used to own it never realized or else never appreciated the fact that in order to get the machine to work, you had to wait faithfully for it to get in receiving mode. And if you turned it on any time of the day, it never got there. It only worked at night.

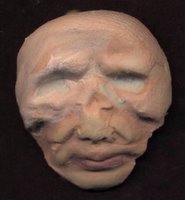

Some nights I'd half-wake up at midnight or two in the morning and turn it on. I'd get the crackle, the ozone, the black screen, then, slowly, dark gray stars would appear here and there, becoming static in gray and black, pal

e gray and black, and finally stark white and black. This process could take 20 minutes, 30 minutes, or seven weeks in kid time. The curious thing about black and white static is that to the human eye, especially eyes that are watching intently, colors are perceived. Eventually the static created fields that coalesced into moving shapes. All this time the sound was going from white noise to static-y pops to snatches of dialogue and music within the static curtain.

It didn't occur to me at the time - and I doubt it still - that late night TV signals out of New York City in the 1960s were the result of programming decisions made by rational people. These signals seemed to come from somewhere beyond the realm of normal reality. They were one third strange old movies, one third the voices and images of ghosts, people now dead but living odd lives on the tube still, and one third the garbled audio hallucinations of an almost sleeping eleven year old.

The only movie I actually remember watching on my ghost TV was Fellini's

La Strada. I fell in love with Giulietta Masina's perky little clown face. I couldn't read the subtitles for all the snow, but I didn't need them to figure out the primal plot line. I think what inscribed the film into memory was the way it evoked feelings of both joy and sorrow in me. That was new and a far cry from prime time on my parents' TV.

Night plus static plus faith plus lack of sleep equals feeling emotion, seemingly the only one alive.

"Don't tease the bear."

"Don't tease the bear."